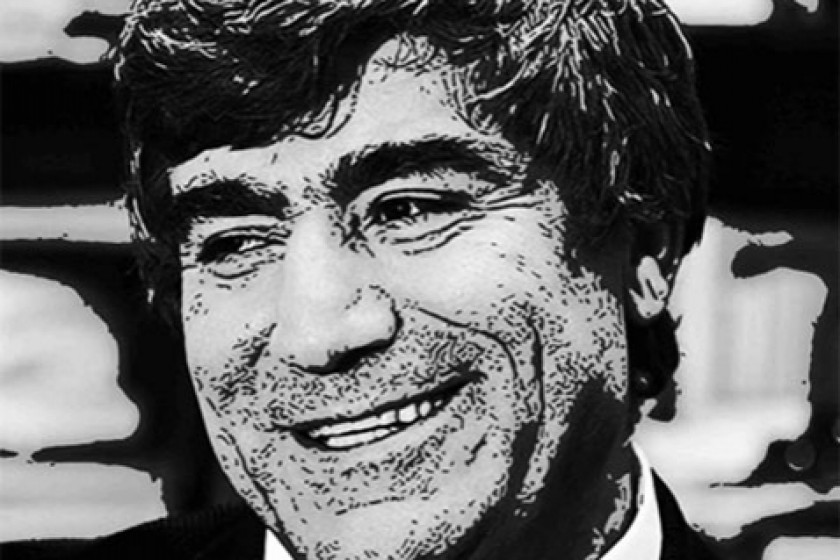

Armenians Must Understand that Hrant Wasn’t “1,500,000 + 1”

By speaking about Armenian-Turkish relations, Hrant Dink offered us a new blank sheet of paper on which to draw.

And he regarded as important what colors we would use to color that paper. For Hrant, it was an incontrovertible fact that Armenians and Turks, having lived through a long and bloody history, are two neighboring peoples “split” by calamities and upheavals for whom, as it stands now, any line of contact remains a utopia.

Let me explain.

Hrant believed that an Armenian sees a Turk from various vantage points and with various approaches. Geography makes this so. There are various types of Turks depending on whether the Armenia lives in the diaspora, in Armenia, or in Turkey. And in all of this, Dink often said that if the diaspora isn’t inclined to at least change its stereotypes about the Turks, nevertheless, it must free itself from its ailments.

The Turks wasn’t a closed theme for Hrant. Rather, it was an evolving, ever-changing society. The best example of this approach is the thousands that marched behind his coffin and who today haven’t forgotten to write the following words on the walls of Istanbul or Ankara – “Hrant Akhparig, we haven’t forgotten. It’s been seven years and we are here.”

As to the extent that large segments of the diaspora will understand or comprehend this approach is a difficult question because the diaspora is like a delirious person of a walking dead soul wearing hoops of stereotypes, taboos and lament.

Hrant didn’t die so that a new day of lament could be added to our diary.

In 2008, in Beirut, the painter Anita Toutigian drew a small red poster in memory of Hrant that read “1,500,000 + 1”, without understanding that Hrant was not that additional “1”. He didn’t die in order to assume that mission. But for wide segments of the diaspora, so accustomed to lament, tears and crouching in a corner retelling the same stories, it was easy to paint such a picture of Hrant.

Hrant never spoke of mourning and he never struggles in its name.

And if segments of the diaspora wrote anything, they wrote about that mourning. If they marched, they marched for that mourning. It was easy for them to preserve the deceased in their delirious bodies. They loved the pain of mourning, because that love, that overall flirtation, demanded nothing at all. On the contrary, it was easy to cry behind the deceased. It was easy to sit and “enjoy” that celebration and then to sit at the memorial meal and then to wait a longtime to again digest, to smell and decompose the deceased.

Hrant was opposed to all this. And thus, it is unacceptable and unbearable to call him “1,500,000 + 1”.

In one of his works he writes:

“Time and again, I have written and spoken to my brothers in the diaspora to put aside and reject the concept of the Turk because living in such a mental state is, at the very least, not healthy.”

These words are proof as to how well Hrant knew us. He knew very well that we are sick. Throughout the entire diaspora, our adoration of the dead, our preservation of the genocide corpse, transforms us, within our own bodies, into irrational beings, superfluous and worn-out.

Even the martyrdom of Hrant Dink changed nothing within us, and today we are gearing up for the Genocide celebrations, and we are trying to bring that feast to Armenia.

The best way to honor Hrant’s memory is to free ourselves from the mourning.

I truly believe this.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (23)

Write a comment