Armenian Army: Punish the Privates, but Spare the Officers

During my digging around in the Central Court Archive, and after reviewing various military court cases, I come away with the conclusion that rank and file soldiers are meted out the maximum sentences allowed by law for serious offences while their officers are treated much less severely – walking away with one or two years at most.

Various local and international organizations have for years raised the issue of weal government accountability with the ranks of the Armenian military. However, after the Artsakh ceasefire, incidents of assault and murder haven’t decreased in army units. According to various sources, some 1,500 deaths have occurred in Armenian military units since 1994.

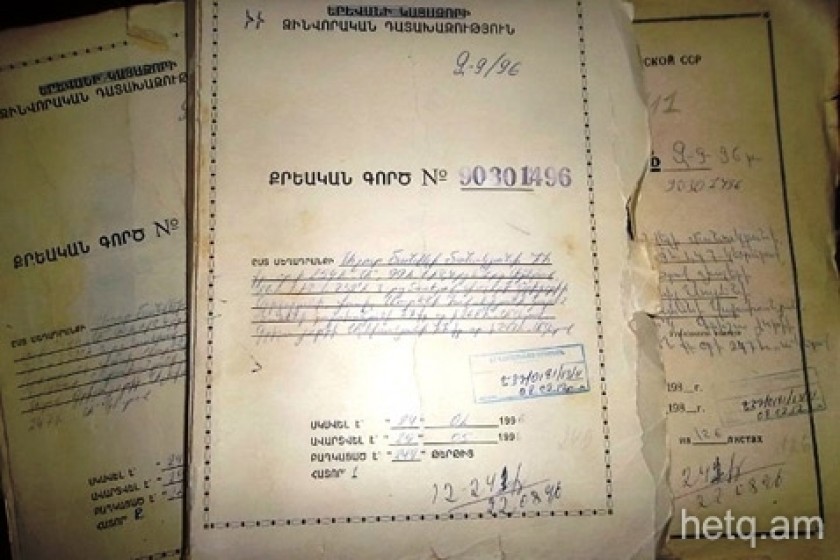

At the archive, I came across a three volume criminal case pertaining to Ashot Manoukyan, who has served 18 years of a life sentence at the Noubarashen Penitentiary. Here, I do not wish to write about any possible judicial procedural errors, but rather how the deaths of the three other soldiers occurred in the post with the connivance of the military unit’s command headquarters.

Private Manoukyan pleaded guilty and was sentenced to death by firing squad. (As of 1991, a moratorium has been declared for all death sentences. In 2003, a presidential decree replaced the death sentence with life imprisonment.)

Manoukyan was twenty years-old when sentenced. During the trial, the soldier stated that he fired on the other three due to an argument over a loan.

Meanwhile, his superiors responsible for supervision at the Pezmashen military unit were given 1-2 year conditional sentences.

The incident took place on February 23, 1996 at the Pezmashen military unit located near the village of Toufashen. The bodies of the three privates – Vladik Osipyan and the brothers Samvel and Sergey Vardanyan – were found a day later. The automatic rifles they had been issued had disappeared. A fourth soldier, Gevorg Khalatyan, was supposed to serve at the same post that day, but he abandoned the post. As soon as the trial started, Khalatyan left for Poland, even though he was a key witness.

In essence, the three soldiers were left at the security post alone, with no command supervision.

Ashot Manoukyan was found three days later at his aunt’s house. He revealed the three missing automatic rifles hidden in the kitchen.

Manoukyan had served at Pezmashen before the incident in question. He had then been transferred to Artsakh and later to Karmir. While at Pezmashen, Manoukyan had loaned Vladik Osipyan 7,000 AMD.

Manoukyan testified that on the day of the incident he left Karmir and returned to Pezmashen to get his money back. An argument broke out between him and Vladik.

“The three of them jumped me,” Manoukyan testified. He says he picked up a rifle and opened fire.

The question arises as to how Manoukyan slipped away from his unit and travelled all the way back to Pezmashen and then made his way to the outpost unseen by any officer. The AWOL soldier even spent a night at Pezmashen.

Some soldiers at the trial testified that, “Officers and junior officers wouldn’t show up at the outposts for months. We’d be eating bread and onions. The only time we went down to the base was to get bread.”

So who was in charge of overall command at Pezmashen? According to the chain of command that person was Senior Lieutenant Vasil Hovsepyan. Supervision of the troops was the responsibility of Colonel Valery Grigoryan. Two other officers – Karen Karakhanyan and Grisha Aleksanyan – were supposed to have conducted spot checks.

None of these four were ever arrested even though charges of official negligence were levied. One was placed under monitoring by command staff, while the other three merely had to sign an affidavit promising not to leave the country. Two of the junior officers were sentenced to two years, but the sentence was postponed for one year given their young ages. Karakhanyan and Hovsepyan each received one year sentences.

By the way, at the end of the court’s verdict we read the words “destruction of physical evidence”. This removes any basis that the case can be reopened.

It’s quite clear that this crime wouldn’t have occurred had there been adequate command supervision at the outpost and had the officers responsible for the welfare of their soldiers actually done their jobs.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (5)

Write a comment