The Body as the Sole Subject of the Senses

Arevik Arevshatian

Arevik Arevshatian

History and theory of art are still the disciplines where traditional conservative approaches and classical value systems reign, resisting change. Canonic dictums by 19th century art critics are to blame for this; their traditionalist language and interpretation models are still utilized by modern day critics as the backbone for their analysis of all art, whether classical or contemporary. Within the last 30 years the global Weltanschauung, concurrently with political and social movements, underwent permutations that brought about the need for a major wave of rethinking.

The past century’s advances (in feminism and gender studies) on the issue of women’s creativity have irreversibly transformed every prevailing stereotype around this. By the same token, associating women’s creativity with applied arts is no longer a valid assertion. International art studies have revealed many Renaissance and Baroque works by women, aspiring at breakthroughs in the perception of this world, thus shattering the mystery of Man the Creator.

The struggle in the 19th-20th centuries for women’s rights and freedom of expression (novels by English and French women authors), the transition from the status of the sitter/model and consumer/audience to that of a creator and scholar, set the stage that made it possible for women to contribute to the formation of the reality around them. The image of the sentimental and dreamy or sly and treacherous woman that had evolved through the male perspective is phasing out. These processes transformed the subjected status of the female body, her sexuality and social role. First and foremost women themselves started to embrace the idea that there no longer were any means of expression considered to be male prerogative, no more dividing lines setting aside the High, i.e. male creation/occupation. The suffragist, feminist, gender and social movements eventually found their expressions through art. I believe that this became possible only after assuring the bodily/physical presence of the woman in the society. Nevertheless the past 30 years demonstrated that there exists no homogenous female perspective, and not every work by a woman author may relate to feminism or gender. Still, almost every cultural context has gained in diversity and pluralism by virtue of representation of reality through the female vision. These developments were not isochronous. It was first necessary for women to gain access to fundamental methods of learning and studying art. Be virtue of an outlook gained through their own experience, works by women have become today an inseparable presence in fine arts. Then again the methods and styles that are ascribed today to women’s art gained in persuasive power after some theoretical rethinking. The world’s art heritage, accumulated over centuries, along with its perception in the context of new technologies, afforded possibilities for divergent, often contradictory interpretation. The replication and multiplication of images, their use in advertising, active penetration out of the private space into public spaces affected the representation of the human body. The use of images en masse in the media became commonplace, where especially the female body became part of the attractive packaging of products. This encountered the disgruntlement of the public at large, as well as in art circles. Such a stylization of the figurative, which used to be the basis of fine arts, threw a gauntlet to the achievements that pertained to non-standard perception of the body.

Whether clothed or not, the portrayal of the human body has always been and still is most controversial in just about every culture. Le Corbusier and Amedee Ozenfant believed in a strict hierarchy in arts, culminating in the capture of human form. One of the many reasons behind the controversy, perhaps the most important one, is that the body is the sole subject of perceiving reality. The body connects us to birth and death, pain and pleasure, fairness and violence. That is, if one fails to remember the body, to see its images, one may even not notice that the reality is out there. Like a man waking up or coming to senses after a swoon starts to fumble the body to gain assurances of wakefulness, so does a pictured body register the reality in all of its incarnations. I believe that methodological distinctions between the male and female approaches to capturing the reality are most salient in works that portray the body. These works embody open messages intended to lure a resisting onlooker into a contemporary analysis and a rethinking of culture and art. A study of all these issues is of utmost importance particularly as applied to the post-soviet space. The Soviet period afforded important and progressive advancements for women, such as equality of men and women and equal rights to education, thus leaving an undeniably positive effect. At the same time the Soviet totalitarian system, following the logic of the cold war, did everything to demonstrate its cultural superiority, impairing integration processes in art and culture that comprise the texture of modern day art and its studies.

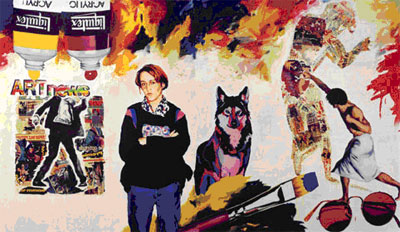

I have made an attempt to present my own findings in the framework of this exhibition. They are in logical sequence to women’s exhibitions that I had curated: Simply and Against, 1994; Mono Polis, 1997; Creative Syntheses, 2005, where I tried to present, in various contexts, developments in the creative methods of Armenian women artists. Under the heading The body as the sole subject of the senses I am presenting several artists who, like me, are women and happen to hold the same views.

Armenian-English translation by Artashes Emin

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment