Director of “Grandma’s Tattoos”: ‘Loving Armenia Must Be a Two-Way Street’

Suzanne Khardalian talks about her experiences during the shooting of the film, Armenian identity and the plight of Middle East Armenian communities

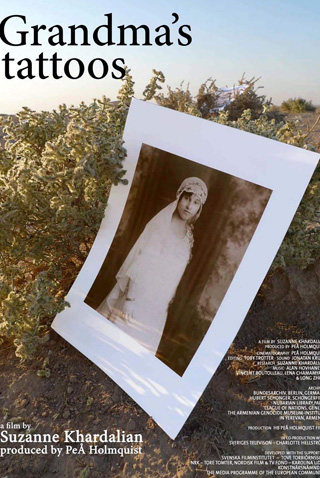

Suzanne Khardalian is a film director probably best known to Armenians for her 2011 documentary “Grandma’s Tattoos”.

Born in Lebanon and now living in Sweden, Khardalian has also directed other films on the Armenian Genocide including “Back to Ararat” (1988) and “I hate dogs” (2005). She has a Masters from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.

I recently spoke to Khardalian about the Armenian Genocide, the making of “Grandma’s Tattoos”, and recent events in the Middle East.

“Grandma’s Tattoos” is basically a film about your grandmother who survived the 1915 Genocide. What motivated you to make such a film?

The truth is that when I started to shoot the film it never crossed my mind that I would wind up talking about my family. What I found interesting was searching for material about the vicissitudes that women who had experienced genocide were burdened with. I wasn’t only interested in the Armenian Genocide but also the Rwandan Genocide.

So how did you start the project?

I began to have conversations with Rwandan women. When I was there, strange parallels surfaced and their stories reminded me about what had happened to Armenian women during the 1915 Genocide.

What do you mean?

For the most part, what attracted my attention were the narratives of those who survived the Rwandan events. For example, stories about the slaughter of pregnant women, the beheading of young kids, or the rape of women and girls.

What year was this?

I started filming in 2008 and finished in 2011. At the time there were no academic articles or materials on these topics.

Why? Are you saying that there were certain taboos for Armenians?

Naturally; because it was almost a banned topic to speak about. In a strange way men don’t want to talk about this issue. For instance, during my encounters they [men] would strangely be opposed and it was impossible to open those pages. They would even ask how is it possible to speak of such things, invoking their Armenian male pride. Another interesting note in this regard is that those who wrote our history have adjusted events to suit their conceptions.

Has it always been like this?

Generally speaking, yes. If we read those works on the Genocide, whether memoirs or survivor accounts, we notice the general lack of narratives on women. And even if they exist they are quite perfunctory.

So where did you fund the first material on this subject?

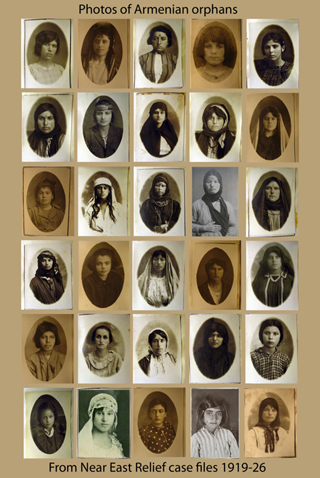

I found many photos of tattooed Armenian women in the collection left by the Danish missionary Maria Jacobsen, a great friend of the Armenians. These showed women with tattoos on their hands, neck and face. Amazingly, no one had asked what these tattoos meant.

As you mentioned, the main protagonist of the film is your grandmother.

|

|

I never was aware, and it never occurred to me, that the most personal narrative about the Genocide was concealed in my family. Yes, the film revolves around my grandmother. I should add that before the dark passages of my grandmother’s odyssey came to light, there was an attempt within the family to forget the past. This is characteristic of many who escaped the claws of the Genocide. No one dared to broach those past events or to question the grandmothers living with them about the past.

What can you tell us about the tattoos?

It took a great deal of time to finally understand the meaning of those tattoos. Those tattoos became my obsession. During the making of the film I met a Kurdish woman who was a fortune teller. She explained the intricate process involved in making the tattoo ink.

Please describe it.

They would remove the bile of an animal killed as prey and mix it with the milk of a woman who had just given birth. They would then add the remaining ashes of a fire. All this was performed in a secret fashion, reminding one of a magical ritual.

Who performed the ritual and why?

It’s a ritual unique to Turkish, Kurdish and Arab tribes. Each tribe has its own signs. For example, the tattoos on my grandmother’s hands were the signs of a Kurdish tribe and are different from Arab ones. As for their significance, it derives from the need of each tribe’s leaders to distinguish their women from those of another ashiret [tribe]. Such separation was especially important when it came to exchanging prisoners. Just imagine that in my research I even came across tattoos that incorporated Christian symbols.

To what would you attribute this?

This is simply a result of discrimination, in order to say that a certain woman comes from a Christian background and was married to a Christian. In reality, this was one variant of a policy of discrimination.

There are scenes in the film where one is taken through the museum at the St. Nahatagats (Holy Martyrs) Church in Deir Zor. Sadly, that church today lies in ruins. Who would have imagined such a thing could have happened?

It was very difficult for our camera crew to get permission. I even remember that a BBC crew was evicted from Deir Zor the same day. After much difficulty we were allowed to photograph. There were many different emotions. The saddest was we didn’t even have the right to pay homage to our dead or stand watch over their collective and open graves.

Had you ever thought that such a thing could happen?

Yes. When I was there I heard on several occasions that Turkish officials had visited Deir Zor and had taken Ottoman Turkish archives back to Turkey. Many knew about this but no one could say anything.

There was an effort to remove the traces left by our martyrs. In reality, this isn’t a new policy. It always existed but they were waiting for the right time. Why did Turkey feel the need to remove Ottoman archives located in Syria?

In this regard, do you have anything to say about the slow response of Armenians?

Great changes and important events are occurring all around us and amidst this turmoil we remain confused.

The most dangerous aspect is that I see no effort to devise long-term solutions to the challenges we face. Every day we take one side or another but we manifest no willingness to take these momentous issues seriously.

In the case of Syria for example, we sit by with our hands folded and watch. It’s the same regarding Aleppo or what is happening now in Kesab. My fear is that as a people we merely pay lip service. We all talk about these things but it escapes me why we wait to look for fundamental solutions. We don’t want to go beyond talk, or else we don't have the resources to impact on events taking place.

I would like to ask the following. What will we do if these same events are repeated in Anjar or Bourj Hammoud tomorrow? We all know that that Lebanon is burdened with over one million Syrian refugees. Isn’t this a serious challenge for us?

So, in this regard, you’re a pessimist.

No, I’m not a pessimist. But the future plight of Armenians in Lebanon is of great concern for me because, as I’ve noted above, that community is facing a very serious challenge.

And if we continue to remain hands folded, in the face of this, then it means something else. Without a doubt, we must either take the communities of the Middle East under our wing or else let them disperse across the world like the seeds of a pomegranate and thus disappear. The seeds will give fruit but others will reap the bounty, not us. The most important is that I would not want to hear a few years later that the regions heralded as the “Armenian fortress” are threatened.

The last scene in your film is shot in Armenia. It’s evident in the scene that you have a certain message to impart.

If you have a sliver of land, a house and a church, if you have a sanctuary, and if your cultural heritage is created on that land, that is the key to your survival. The only environment where our identity continues is Armenia; not Los Angeles or anywhere else.

In this context we have serious issues to contend with. Would you agree?

Yes, because in Armenia today there is a sizeable segment of society that presents itself as a know-it-all. Its members proclaim, “We are supermen who know everything. Just give us money and don’t go poking your nose around.”

This psychology has a negative effect on Armenians in the disapora and prevents better relations. This situation creates certain alienation and the supreme issue for us all is to fight against such situations.

I believe that the love that exists regarding Armenia must not be a one way street. We frequently speak about Armenians in various communities relocating to Armenia but just how ready is the society in Armenia ready for such a thing.

We must really research this relationship and provide a positive basis in an organized fashion. We have no other path.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment