We Sing and Dance to Survive

“I melt and waste away, I burn in fire. Tell me when my child will return, I count the days,” sang Sonya Chichyan.

But she is not a singer, nor did she write the song. When asked who the author was, she replied, “He who is the author of everything.”

Twenty years ago, Sonya Chichyan lived with her large family in thevillageofGetashen, inLower Karabakh. Her husband was a laborer working on construction sites inRussia– he would return in the fall and leave again in the spring. The money he made had allowed them to build a large two-story house. They had three boys and one girl.

Their lives were radically changed when, in 1991, the Azerbaijanis – with the active participation of the Russian army – began “passport checks” in the south of Nagorno Karabakh and the Armenian villages of Lower Karabakh. As a result of Operation Koltso (Russian for “ring”), as it was called, tens of villages were emptied of their Armenian residents, who became refugees and fled toArmenia.

Sonya, however, does not use the word “refugee”. “We have been deported,” she said, and explained the difference. According to her, a refugee is a person who leaves his or her birthplace for various reasons, sometimes by force. Some of the Armenians fromBakuorSumgait, for example, could be considered refugees. She said that deportees, however, were those who had been rushed to helicopters and relocated in a matter of hours.

Sonya, however, does not use the word “refugee”. “We have been deported,” she said, and explained the difference. According to her, a refugee is a person who leaves his or her birthplace for various reasons, sometimes by force. Some of the Armenians fromBakuorSumgait, for example, could be considered refugees. She said that deportees, however, were those who had been rushed to helicopters and relocated in a matter of hours.

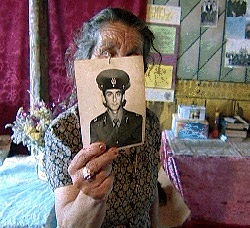

Her youngest son was serving in the Soviet army at the time of the deportation. “He was already coming home, he had been discharged. Then he found out that he couldn't – what home was there to come to?” the old woman recollected and said that it was only after a long search in Armenia that she was reunited with her son.

“That is deportation,” she sighed, “I had no idea what village this was, or where it was located.”

Sonya Chichyan lives in thevillageofNorabakin the Gegharkunik Marz. They were brought to this village – formerly inhabited by Azeris - immediately after the deportation. Winter here lasts exactly half the year and nothing can be cultivated except for potatoes. Unable to get used to the conditions here, two of her sons left forRussia. One of them now lives inOrenburg, while the other resides in Armavir. Her daughter lives with her own family in the Karabakh region of Kashatagh. Her husband died three years after they came to Norabak. His early death was the result of torture by Azerbaijani and Russian soldiers. He had been taken hostage on two occasions and released in terrible condition.

Sonya Chichyan lives in thevillageofNorabakin the Gegharkunik Marz. They were brought to this village – formerly inhabited by Azeris - immediately after the deportation. Winter here lasts exactly half the year and nothing can be cultivated except for potatoes. Unable to get used to the conditions here, two of her sons left forRussia. One of them now lives inOrenburg, while the other resides in Armavir. Her daughter lives with her own family in the Karabakh region of Kashatagh. Her husband died three years after they came to Norabak. His early death was the result of torture by Azerbaijani and Russian soldiers. He had been taken hostage on two occasions and released in terrible condition.

“When the chaos started, we could have left earlier, but we thought, ‘We were born in Getashen, we've built houses here and have family, and we will stay in Getashen,' but that was just fantasy.” Only her youngest son lives with her in Norabak. “I have already forgotten my children. I've forgotten their curly hair and the way they speak. I might not even recognize them when I see them,” said Sonya, at the same time justifying her children's actions. “One can't blame them, it is very difficult to come and go. Could I go if I wanted to? I don't think so.”

Sonya receives a pension of 10,000 drams. At 333 drams a day, she cannot even dream of seeing her children. In the fall, she works at the potato harvest, despite her old age. She receives 2000 drams daily for doing so, but that is only short-term work. Nevertheless, she does not complain of her financial condition. Her main objective is to maintain her current standard of living, which she is working very hard to do.

Sonya receives a pension of 10,000 drams. At 333 drams a day, she cannot even dream of seeing her children. In the fall, she works at the potato harvest, despite her old age. She receives 2000 drams daily for doing so, but that is only short-term work. Nevertheless, she does not complain of her financial condition. Her main objective is to maintain her current standard of living, which she is working very hard to do.

The poems that she recited seemed to be a confession of sorts for Sonya – “My smile is fake;” “My mouth sings of joy while my soul of sorrow and suffering;” “I try to walk around happily;” and other such works.

“Did you write these lines?” I asked her. “I wrote some and others I borrowed and adapted to my life,” said the deported woman from Getashen and – to further illustrate her way of life – turned the music system on and danced alone in the narrow corridor of her Norabak home.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment