Real and Imaginary Problems in the Village of Myasnikyan

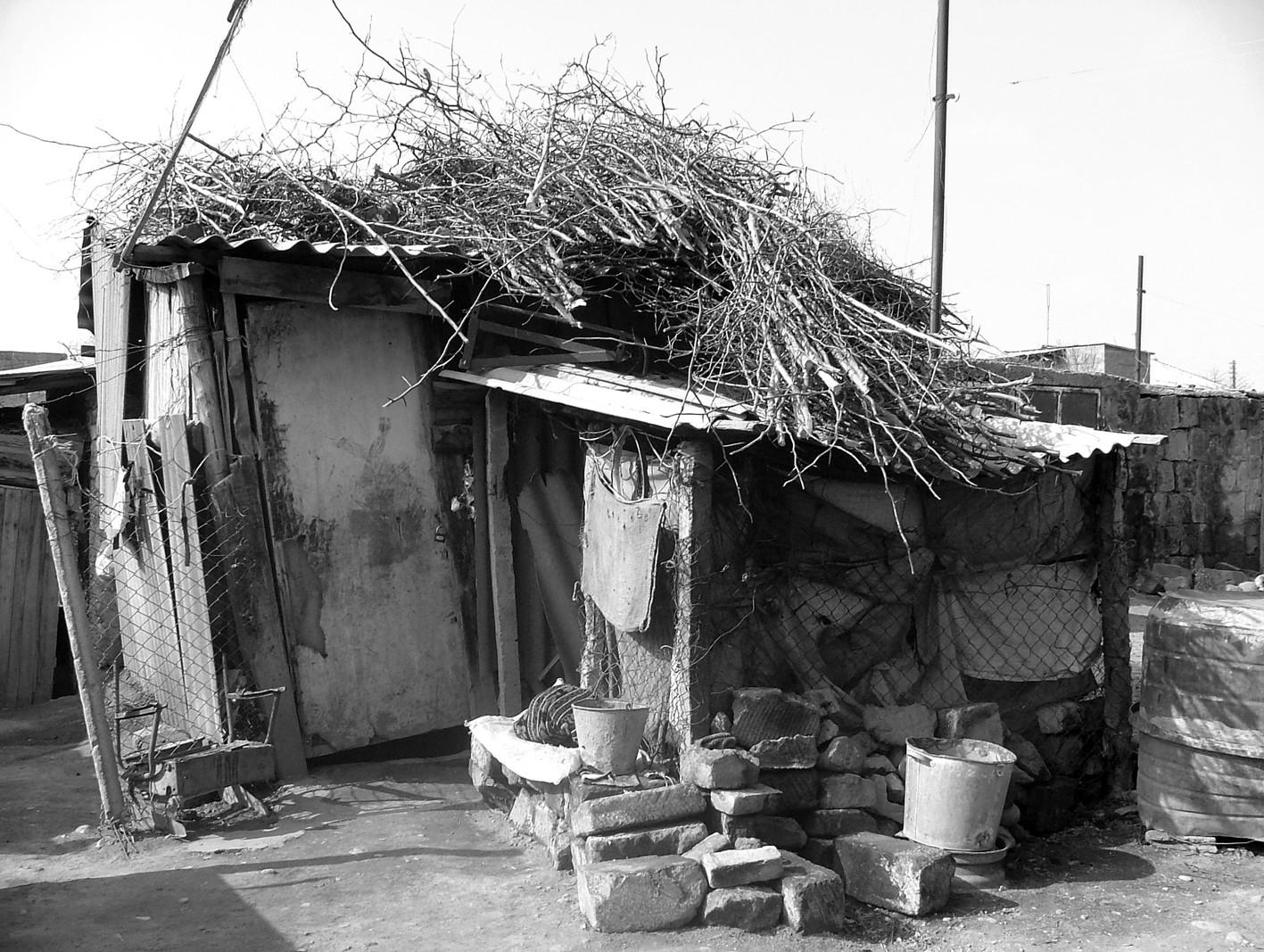

Water, a café, paved roads - these are the most important things required to completely satisfy the residents of thevillageofMyasnikyanin the provincial region of Armavir.

The villagers have problems with both drinking and irrigation water. They buy their drinking water from Talin at 50 drams per bucket. One ton of water lasts a family on average five days. Irrigation water comes from the Akhuryan reservoir.

The villagers need a café in order to have a place to gather and chat. Otherwise, men gather in the village club or outside shops, and women are left out. There is an abundance of shops and taxi services in the village; there were three taxi stands in our immediate vicinity.

Journalists are not particularly welcome in the village. They are perceived in the same way as charity organizations. “If you're not 100% sure that what you write will provide us with some benefit, why have you come here?” But, nevertheless, they complained of their difficult life – who knows, it might help.

There are 4,460 people living in Myasnikyan. The villagers moved here mainly from the provincial region of Shirak and Javakhk, and fromSyriaafter World War II; there are also some refugees fromBaku. There are many Kurds and Yezidis.

The Armenians have a good relationship with the Kurds and Yezidis of the village. However, you can still notice in this village the Armenian national trait of keeping apart from the other ethnicities living in our country.

“We live in peace and harmony, but that is through the grace of the Armenians,” said the women working in the Sanitary and Epidemiology Station. It was still cold in the building and they had all gathered in one room, drinking coffee and chatting, “Otherwise the Yezidis are like this – if you say one thing to any of them, they will all attack you together.”

Andranik Petrosyan, head of the village administration, assured us that this attitude of the villagers towards the Yezidis was in fact an expression of jealousy.

“If a Yezidi had 150 heads of sheep five years ago, now he has 1,000 ewes. They used to live in tents, and now they live in nice houses. This is because they are hard-working people, in contrast to the Armenians,” said the village head.

Complaints about unemployment were abundant in the village.

Most of the villagers do not have regular jobs; they mostly work as day laborers. Many of them – both men and women – work in the vineyards bought by Argentinian-Armenian Eduardo Ernekyan.

“It's indentured servitude,” said two men, standing near the House of Culture, in contempt. Both were unemployed.

The villagers said that many of them had land adjacent to their houses. However, it was not profitable to cultivate these plots as the costs of fertilizer and other necessities were too high.

A woman who works is not favorably perceived here. Many think that she has reached the edge and has been forced to work to support her family. Or she does not have a husband and has to feed the children herself.

The janitor at the Sanitary and Epidemiology Station, Aghavni, has been living here for fifty- one years now. She lives with her sister and niece. She said that her 23,000-dram salary barely pays for her food. That leaves the diabetes medication she has to buy as well as payments for electricity, water and gas.

“Our village is supplied with natural gas. But in all this time nobody has come to check the safety standards. However, if you delay payments by fifteen days, they don't hesitate to come over and turn off your supply,” she complained.

“70% of the people who used to work in the Soviet state-owned farm ( Sovkhoz) are abroad. If it weren't for them, these people would be unable to survive. There is no work, no other way to survive,” added Aghavni. The villagers call their village the “4 th Sovkhoz ”.

“Enough complaining,” interrupted one of the women, “It's better if you tell us if you're going to vote.”

“Definitely.”

“Who is going to get your vote?”

“Whoever pays me money to vote. Listen, girl,” she turned to me, “Nobody is begging here, but they are selling their votes. If some parties have money to give to the people in exchange for their votes, then I'll be one of the people getting that money.”

“But what if nobody pays?”

“Then I'll vote any way my mind dictates at the moment.”

Most of the villagers were indifferent to the upcoming parliamentary elections. Some of them did not even know which elections were around the corner. One woman asked, “What elections? Are we going to choose a new village head?”

The residents of Myasnikyan like their village head. They do not explain the problems they face in the village as because the “village head is not thinking”, but rather because “the village head is thinking but his efforts aren't working out.”

Village Head Andranik Petrosyan had a different opinion.

“We don't have any problems in our village,” he said. “Thank God, the village is near the town (12 km); we're not cut off from the rest of the world. The only problem is irrigation water. Three hundred hectares of land dried up last year because there was no irrigation water. I don't think this problem will be solved anytime soon. But we will have drinking water starting in May, thanks to the German company Nor Akunk . The water meters have already been installed.”

Petrosyan considered the complaints about unemployment to be absurd.

“There is at least one person from each family in our village who works for the state. We have many state organizations – the village administration, the House of Culture, the school, kindergarten, polyclinic, emergency hospital, sanitary and epidemiology station, gas supply office, electric power station, fire department, railway station. Ernekyan's company, Agatha, needs workers but they can't find any. They pay a daily wage of 3,000-4,000 drams. But they (the villagers) consider themselves above day labor,” said Petrosyan and continued, “This village has always worked in farming and animal rearing. We had around 1,000 hectares of vineyards and fruit orchards in the past, where 16 field brigades - each consisting of 30 workers - used to work. Now there is someone with 2,300 hectares of land here who needs workers. Why don't they work? They can make up to 5,000 drams a day if they want. But instead, they sit and home and think, ‘Let them give me a charity allowance of 18,000 drams a month, we'll get by.' They have gotten used to the Soviet habit of not working and getting paid for it.”

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment