From Kobanî to Yerevan: Raising 4 Kids On His Own, Serop Tovmasian’s Job Prospects are Limited

Hrant Galstyan

For the past four years, Serop Tovmasian has been raising four kids on his own.

He sends nine-year-old Mike to a special needs school every morning and then starts preparing a meal for his children when they return home from school. It’s then time to squeeze in the rest of the household chores.

There’s no time for work. Serop's savings from Syria will soon run out. The organization now paying the family’s rent has said that this assistance will soon end as well.

Serop, and the families of his two brothers, moved to Armenia in September of 2015. They fled Syria when ISIS attacked the town of Kobanî, on the Syria-Turkish border, where they were living.

Serop says that his wife died two years before this and that the “bearded” extremists killed Hovsep, one of his brothers, when they attacked the town. The families of the three brothers, along with thousands of other Syrians, crossed the border into Turkey, fleeing the advancing ISIS militants.

Serop and his family found refuge in the refugee settlement in Suruç, 46 kilometers south-west of the town of Ourfa. There, they lived in tents for eleven months.

Aram Ateşyan, the Acting Patriarch of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, visited the family in Suruç and organized their relocation to Armenia.

“I asked how the conditions are there. He said they’d give us a house for nine months and pay the rent. They’d also give us three months’ in cash assistance until we get on our feet. We came and they just gave us one month’s assistance. That nine months for the rent turned into six,” says Serop, adding that the family gets by on personal savings.

Serop was an ironmonger in Kobanî and repaired cars. Shahen, his 14-year-old son, assisted him. After they left Kobanî, the town was razed to the ground. So too were their house and store.

Mr. Tovmasian is worried that he cannot provide for his children here in Armenia. “How can I get work and take care of four children at the same time? Who’s going to cook, wash and take them here and there. It’s been four years that I’m doing it by myself.”

In Syria all the Tovmasian families lived together. His brother’s daughters would take care of Mike. Now, they too are looking for work. In addition, Mr. Tovmasian says that only he understands Mike, who didn’t speak in Syria. He’s started to utter a few words and to count in Armenia. Mike now attends a special needs school called Arevik created for Syrian-Armenian children.

Like his siblings, Mike sometimes equates long noises to the sounds of explosions and gunfire back in Kobanî. “It’s not easy. When someone has fled from one country to another, escaping a war, the brain doesn’t work normally. The person is disillusioned with life. It takes time to settle down. We are totally cut off. Do you understand? When these kids sleep, they hear the sounds of tanks, of war, and are frightened. They think they are still in the midst of war,” says 53 year-old Serop.

Kobanî is a majority Kurdish town that had Arab, Turk and Armenian minority populations. There were only eight Armenian families in the town before taken over by ISIS. Three of the families were the Tovmasians. Serop recalls that decades ago there were many Armenian in Kobanî. There was an Armenian school in the town and Serop attended it until the third grade.

Twenty years ago, when most Armenians left Kobanî for Aleppo or elsewhere, the school closed. Serop’s children learnt Arabic in school and picked up Kurdish from neighbors. Late, when they fled to Turkey, they learnt some Turkish and English.

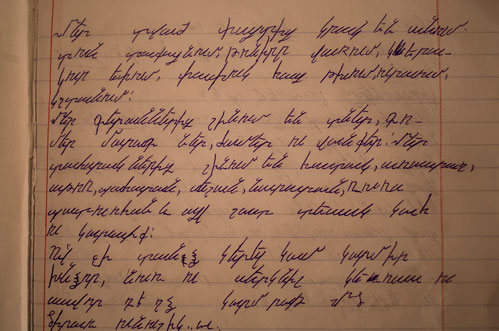

Today, Maral, Shahen and Raffi (in the 4th, 7th and 8th grades respectively) are learning the Armenian alphabet. At school, they find it hard to follow the lessons and aren’t getting additional hours to learn Armenian. Teachers refrain from asking them questions in class.

|

|

“I write whatever they write on the blackboard. That’s what they told me to do,” says Maral. “I just look. I’m already fed-up. No one talks to me and I’m not learning. I just listen for seven hours, nine hours,” says 14 year-old Shahen.

|

|

Raffi and Shahen are getting private Armenian lessons paid for by a benefactor. The children want to receive lessons in the language several hours a week at school. They sometimes find the Armenian spoken in Armenia difficult to comprehend.

Serop says that employees in a shoe store where his brother’s daughters were working refused to work with them because they don’t know Russian.

The family mainly speaks Arabic or Kurdish at home. Serop says he tries to speak Armenian with them so that they learn quicker.

Photos: Narek Aleksanyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (4)

Write a comment