Yezidi Village School: Coal Stoves are Relics of a More Prosperous Past

Vahe Sarukhanyan

The school in the Yezidi-populated village of Tlik, in Armenia’s Aragatsotn Province, is a real antiquity.

Preserved in the one-story building, constructed in 1956, are brick ovens in which coal was once burned. The school is now heated with oil.

Another blast from the past is the wall near the teachers’ study displaying the names of Tlik residents who fought in the Great Patriotic War (WWII).

The school’s bathrooms are located outside. In warmer weather, gym classes are also held in the school yard. There were no classes on the day that Hetq visited the school. Teacher Alik Mstoyan said that classes had been cancelled due to the cold weather. That same day, villagers were celebrating Aida Sltan Ezid, a Yezidi national holiday.

Tlik is a village of 94 souls a stone’s throw from the border with Turkey. The ruins of Ani lie on the other side. All the school’s 21 pupils are Yezidis from Tlik. However, only one of the nine teachers is Yezidi – 30-year-old Alik Mstoyan. The rest are Armenians from nearby villages. Long-time school principal Vahagn Martoyan is from Aragatsavan.

Alik Mstoyan shows us around the empty school. He’s been teaching Yezidi language and literature classes for the past year. Prior to Alik, the former mayor of Tlik was teaching these classes. The mayor has since left Armenia. Tlik, a flourishing village in Soviet times, now only has eighteen households. Nine have relocated to Tlik from the Armavir village of Araks.

Alik says that this school year the school enrollment has increased – from 20 to 21. Last September, there were two kids in first grade. Next September, they expect five.

School goes to the ninth grade. Only five classrooms are used, however, because some of the classes have been combined. For example, there’s only one pupil in seventh grade. Alik shows me the attendance sheet. There’s only the one line. We smile, hiding a deeper sadness. With six pupils, the fifth grade is the largest class.

The wooden floorboards creak as we walk around. The old desks, that have seen several generations of children, strike my eye. They stand in sharp contrast to the new white windows and doors installed in 2012. Alik, who graduated the school in 2001, says that in his day the doors and windows were broken.

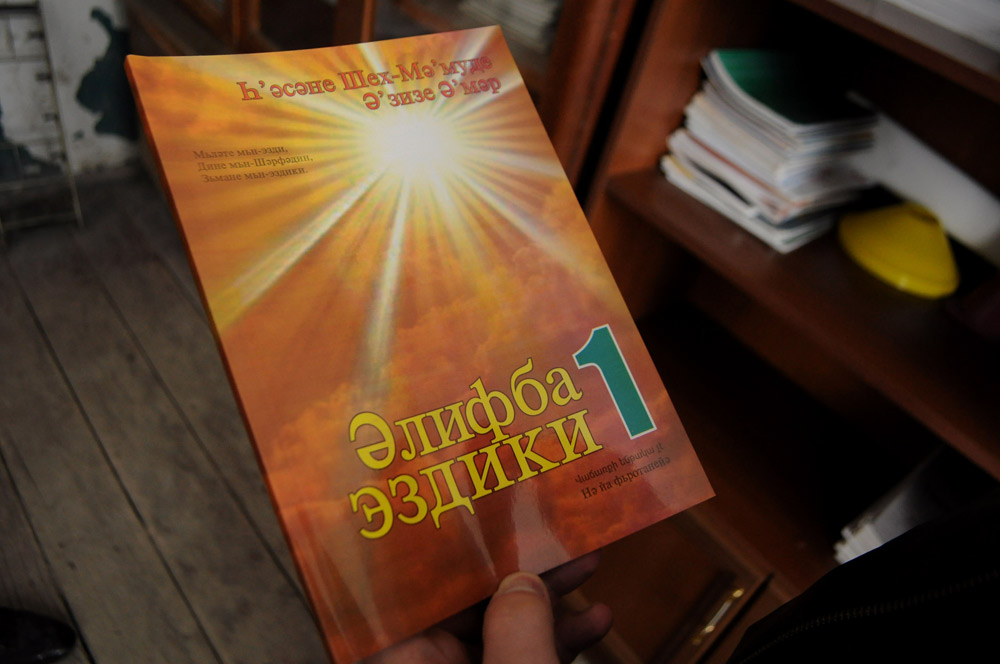

The newest books I see in the cabinet in the teachers’ study are the Yezidi textbooks. There a club and a library in the village located in the building housing the mayor’s office. When I ask Alik if the pupils make use of the library, he smiles and says, “As if they study a lot and are reading.”

Alik says that upon graduating the ninth grade, most of the pupils have no desire to continue their education. He tells the story of a bright girl whose parents forbade her to continue her education, despite the exhortations of the school.

I ask if this is due to the tradition of marrying off girls at a young age or just the general mindset. “It has nothing to do with tradition. It’s the mindset of people,” Alik replies, stressing that everyone, male or female, needs a good education to survive in this world.

Photos: Narek Aleksanyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment