A Repatriate’s Response: “It’s not what I have come for”

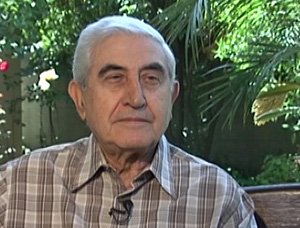

“I was young. The elders would gather in the village where we were staying. They would talk and tell me – look outside. No one listened,” recalls Hakob Bashmakyan, a repatriate from Iraq (1947) who presently resides in Montebello (California, USA).

After moving to Armenia, many of the repatriates had the sense of fear and fright trying to recall “sins” from the “past life” that could have resulted in violence and pressures against them, as well as exile. “We were a mother and son. My father was a Tashnag. If they found out, we too might have been exiled. But no one informed on my father,” said Mr. Bashmakyan.

If they somehow managed to shun violence, pressure and exile, then the inconveniences of Soviet life would “haunt” immigrants throughout their lives. Perhaps that is why regardless of whether the narrator or his family have been subject to political persecutions or not, in all interviews he speaks about the violence and pressures, and exile by confidently amplifying and exaggerating numbers.

Zabel Chugaszyan who immigrated from the USA in 1947 and presently lives in Los Angeles, (California, USA), claims that during the night of June 13 and the morning of June 14, 1949, 160,000 people were exiled from Armenia. “My father used to work in a silk atelier. He was a party member and was told he would be working that night. Before going to work, he instructed us not to open the door to anyone – to just switch off all lights and go to bed. Then he left. He came back in the morning and told us that everybody was being put in cars and taken away.”

Jean Kyureghyan, who immigrated from France in 1947 and presently lives in Paris, says that 50,000 were exiled to Siberia in just two nights. He adds: “They didn’t touch most French-Armenians. Most. I can count the number of families on my fingers, who immigrated from France, that they deported. But tens of thousands of Syrians and Lebanese were.”

The problem here does not lie in the accuracy of the numbers but rather the impression created from the Soviet reality, which was gradually translating into personal experience. Discrimination and various forms of enforcement exercised by the state were also among the factors shaping it.

Most of repatriate, when interviewed, complained that sons (of relevant age) of immigrants were not conscripted. “During Stalin’s time, they didn’t conscript repatriates into the army, arguing that we had no military training. The truth was they didn’t trust us,” recounts Martiros Gyulderyan, an immigrant from France (1947) who then migrated to the USA.

After having graduated with top marks from the Institute of Foreign Languages (Armenia) and pursing a teacher’s career in Byurakan village for two years, Martiros was unexpectedly drafted into military service. He says he was happy at first. The challenges came later. “I was the only one with higher education in our unit. They gave me the lowest job – getting the explosive shells. I was often asked about life in France, etc. I was somewhat naive and told them the truth. One day, at the unit, a KGB representative summoned me and said, “You know what we do to guys like you who seek to lower the morale of soldiers? You will come with me to the office where we will continue our conversation.” During the Stalin era, it was clear that someone could get exiled for at least ten years for something like that. At least. Luckily for me, the next day Khrushchev gave a speech at the Communist Party Congress and exposed the cult of personality policy,” he said.

Such inconveniences caused by army life have been engraved in the memory of Hakob Filyan, a 1949 repatriate from the USA who currently lives in Paris. “In the army, they suspected that I was a spy. The Special Branch would always ask me questions during the three years I served. “When did you come from America?” “Why did you come?” Always the same questions. I told them, if they suspected me of something then why did they accept me in the army,” he said.

Attempts by state security agencies to enlist people were another reason used to emotionally suppress repatriates and urge discomfort towards life in Soviet Armenia.

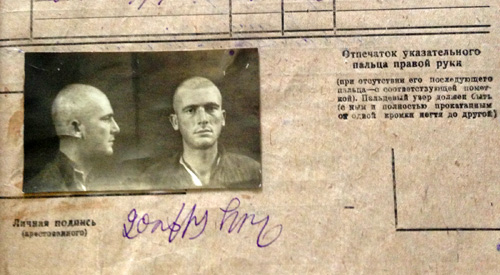

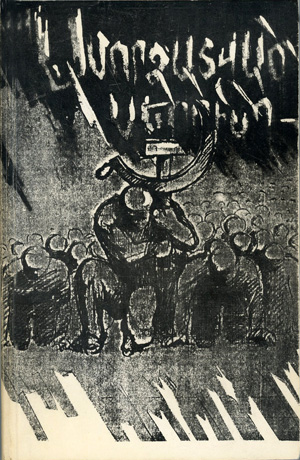

In 1946, Souren Boursalyan immigrated to Armenia from Lebanon, along with his family. A year later he was already a student at the Yerevan Fine Arts and Theater Institute. In 1951, right before he was going to take the last of the state graduation exams, the future film director was arrested.

In his “Emasculated Generation” memoir, Boursalyan writes that the reason for his arrest was that he had refused to serve the KGB. He was amicably asked to “…go to my friend, try to explore his mood, put it down and present it to them,” which he would not do as it would be an act against his own conscience. However, neither could he avoid doing it, as he was being forced to. Thus, he decided to “fool” the Chekists (officials of the security service) ․ Such a careless and not-thought-through intention “earned” him a 10-year punishment, part of which he served in Siberia. He returned to Armenia after Stalin’s death and then left for the United States in 1978.

|

|

Martiros Vardanyan, a 1946 immigrant from Syria who presently lives in Glendale, recalls happened to his brother, citing it as a vivid example unveiling the core of the Soviet regime.

“My brother got admitted to the Department of English Language at the Pedagogic Institute. In early 1948, he was taken to the KGB right from the lecture room and interrogated. He was asked who he was friends with, who is unhappy, who possesses anti-Soviet literature, etc. He was released at 3 am. All that had its adverse effect on my brother. He got sick and was confined to bed for around three months. People from the KGB would come to see if he was sick or was just pretending. Once he recovered and went to the Institute, people from the KGB again showed up and again the same hell began. Fear made him sick again and this time his condition was more severe. To treat him, we were forced to sell everything. After he finally recovered, he quit the Institute and left for a remote village where he worked as a teacher.”

Ingenuity is what saved Paul Antaramian, a 1947 immigrant from the USA who presently lives in Fresno, from an undesirable collaboration with the KGB.

“I was walking on foot when a car approached me. They told me, “hey buddy, get in the car, we’ll take you to wherever you go.” I said “no”. I was of two minds, to get in the car or not. Eventually I got in and they took me to Nalbandyan 104 (the state security building).

They told me they needed my help; information about some people and nobody should know about it as it was a state secret. I said I wouldn’t be able to do that and to their question “why?” I answered that I had just got married and my wife was always complaining that I was talking in my sleep. I don’t remember what happened then, but they never again came after me.”

Apparently, it would not be appropriate to say that all repatriates experienced similar situations, but since there were living in closed communities and communicated with each other, every pressure imposed on their relative, neighbor or someone they knew became something common for all of them and a personal tragedy for each. In addition to other reasons to leave Armenia, such inconveniences of the Soviet life would subconsciously pile up, eventually accounting for their decision to migrate. In the meantime, the KGB was not napping and kept on electing “allies” even from among repatriates that had already applied to the Passport and Visa Office (OVIR) for emigration.

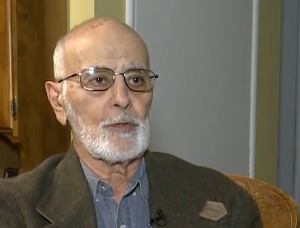

Sargis Mazmanian, who immigrated from Romania in 1947 and presently lives in Los Angeles, recalls one such incident.

“I was called to the OVIR at 5 pm. Two people that were standing there asked if I was Sargis Mazmanian. I said yes, and we entered OVIR, going down the stairs to the basement. There was somebody siting there. He had a very cruel face with a scar. He did not introduce himself and simply asked my full name. To tell the truth, the scene scared me to death. He asked why I wanted to leave. What could I reply given the circumstances other than, “to find my way in life.” He asked me whether I would help them if they agreed, and subconsciously, without giving a second thought, I rose and said, “It’s not what I have come for.”

Translator Ani Babayan

This article is prepared as part of the “Two Lives: The Cold War and the Emigration of Armenians” project financed by National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Comments (8)

Write a comment