The Armenian sex trade - 3

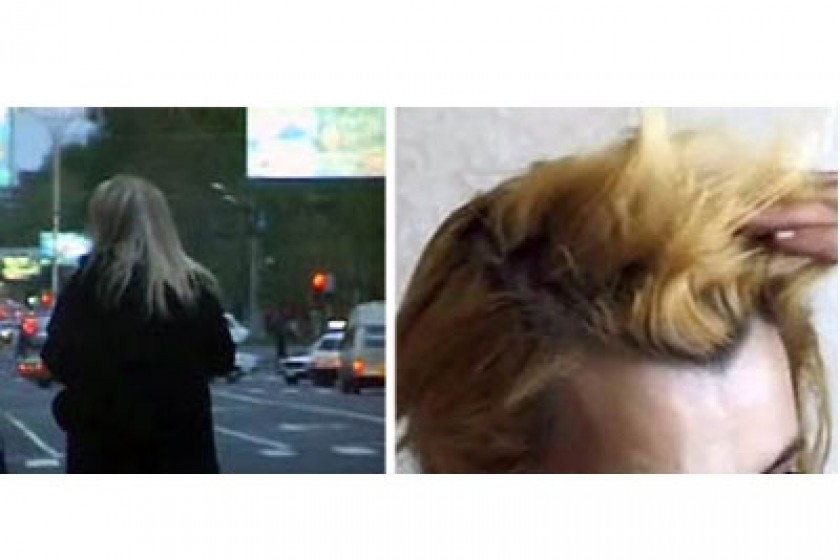

Cropped heads

In the beginning of April, prostitutes looking for clients on Baghramayan Avenue in Yerevan were harassed almost every day; the Arabkir district police department fined the women for standing on the streets under their jurisdiction.

The prostitutes' permanent location had been Mashtots Avenue. When they were threateningly forced off Mashtots by officers of the Kentron district police department, they moved to Baghramyan. "I was standing on Baghramyan Avenue. Police officers said that they had something to discuss with me and took me to the Arabkir district department. They took me to the chief of the police department, Artur Mehrabyan. He said that I had no right to stand in his territory. 'Did the chief of the Kentron department, Hovik Tamamyan, send you to stand in my territory? If he can send you away from his territory, then I can keep you out of my territory, too,' he said, and told his guys to bring a pair of scissors. They beat me and forcibly cut my hair. They did it to all of us," one of the victims, Lilia (not her real name) says.

The police cut off the women's hair on April 6, 2004, on the eve of the Mothers' Day, as they mockingly wished them a happy holiday. For one woman, Veronika (not her real name), it was the second time. The first time the police cropped her hair was in 2001, during the celebrations of the 1700 th anniversary of the adoption of Christianity in Armenia. It was decided then to clear the Yerevan streets of prostitutes to prevent them from harassing visitors to the festivities. The nearly-bald women had to wear wigs to go out on the streets. When I asked one of the policemen what right they had to cut off the women's hair, he responded that the prostitutes are unsanitary, they have lice and they might spread the lice in the police department as well.

The beaten and cropped women decided to complain. After long deliberations, only Lilia had the spirit to lodge a complaint against the police. She applied to the prosecutor general and to the chief of police asking them to take measures "to prevent the law enforcement agencies from such conduct in the future." As she wrote the complaint Lilia kept saying to herself, "I want to know, do I have the right to walk freely in this country? If they fight each other for power, I want to fight for my place. I want to know whether they have the right to cut my hair or not. If they have the right to impose an administrative fine on me, does that mean that they have the right to cut off my hair?"

Lilia took her complaint to the Prosecutor's Office and to the Police. She was told to come back in a week for a response. When I called Lilia she told me that she wasn't going to go back to get the reply; she didn't think any good would come of it. That night I went to Baghramyan Avenue. Lilia wasn't there, but her friends, who were recently harassed by the police, were freely walking the street.

Raids

Police officers periodically round up the women walking the nighttime streets and take them to the Medical Center for Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. During this action, or raid, they take as many women as can fit into a Gazel minibus. These police raids are the main method the state uses to fight prostitution. The women are afraid of these raids; they try to avoid them, but they never resist the police. They get into the minibuses by turns and go to the medical center.

On a routine raid, Senior Operative Officer Tigran Petrosyan told me that they send prostitutes with sexual diseases for compulsory treatment. "Many of them are happy, because the treatment is free of charge-it's paid for by the government. They are medically examined, and if sexual disease are detected, they undergo treatment free of charge," the police officer says.

But the women say they don't like to go to the hospital at night. After they are rounded up, they are forced to spend the night at the hospital, waiting for the doctors to come in the morning. If the raid occurs on Saturday, the women are locked up in the hospital until Monday morning.

"The Dermatology and Venereal Center is worse than a jail; they lock you up there," say women who have been rounded up. They say that they don't need those free medical checkups, for they periodically visit doctors themselves. The night before we visited the Dermatology and Venereal Center, women had squeezed through the windows and escaped.

Business and sex in Bagratashen

Two years ago the organization Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) from Belgium opened a clinic in Bagratashen, a town on the Georgian border of Armenia and Georgia, where anyone can be tested for sexually transmitted diseases and HIV/AIDS free of charge. Armenians, Georgians and Azerbaijanis frequently turn to the doctors here, where they know their personal data is kept confidential.

The MSF-Belgium has chosen the village of Bagratashen because in this transit zone, the risk of spreading sexual diseases is high. People who come to the Bagratashen Bazaar to do business often stay overnight in one of the many inns on the Armenian and Georgian side of the border. Kristina Bayingana from MSF has worked in the Tavush Marz (province) for a year, but still finds it hard to say what the minimum price is for sexual services in the border area. "Many women get some food or other goods instead of money. They exchange sexual service for food for their children. There is no high-level, elite sexual service here. Prostitution is carried out in secrecy. You won't see a woman waiting for a client on the street here," Bayingana says. One of the women who services men in Bagratashen inns, Ashkhen (not her real name), says she and her colleagues can be contacted through acquaintances. Direct contact with a stranger is impossible. The main thing is to escape the attention of law enforcement officers. According to Ashkhen, if police officers somehow find out about a sexual deal, they create problems for the clients and take money from them.

The sex trade in the border area knows no national boundaries. People earn their daily bread any way they can. Often, Armenian women provide sexual services to Azerbaijani men on the Georgian side of the border. Ashken says that she prefers to engage in paid sexual relations exclusively with Armenian men, though some exceptions do occur. "We go mostly with our guys," she insists, and drops the subject.

To be continued

Gegham Vardanyan

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment