Armenia’s Oil-Soaked Storks: Government Agencies Still Searching for Culprits

Photos of oil-soaked storks, Armenia’s non-official state bird appeared in Armenia’s social media last month, causing a minor public uproar.

The birds were spotted along a section of the Hrazdan River, near the village of Dashtavan in Armenia’s Ararat Province.

Government officials in Armenia, evidently caught off guard, hastened to diffuse the situation by sending a team of investigators to the scene.

On August 6, Armenia’s Nature Protection and Soil Inspectorate sent their findings to the Prosecutor General's Office, this according to Naira Aghababyan who heads the Inspectorate’s Department of Public Affairs.

According to Arevik Khachatryan, Head of the Prosecutor General’s Office, the materials were sent to its Ararat Province branch and from there to the Artashat Police Department, where a case file is being prepared.

The problem, centered in the villages of Artashat and Masis, has been in the public spotlight for several weeks. However, much of the attention was drawn to one village, Hovtashen, where environmental ministry and inspectorate staffers had taken one of the oil-soaked storks, unable to fly, to the Institute of Zoology.

An examination of the stork feathers revealed that they contained vegetable or animal oil used in food production. This stork was not the only one; many such birds were found. Some zoologists and environmentalists have called the situation an environmental disaster.

Soon afterwards, the Inspectorate announced that the process of detecting the source of contamination of the Hovtashen storks was continuing, with the Inspectorate and the Ministry of Environment working in conjunction with a group of volunteers cleaning the storks. The ministry, for its part, said that it was focusing its attention on the contamination problem and the declining number of storks in Ararat Province.

Inspectorate unable to determine the composition of the contamination

Inspectorate Deputy Head Armen Hakobyan said the following to Hetq:

“The reason for the contamination of the birds is the presence of an oil layer in the waters around the Hovtashen community. Water samples were taken from the Hrazdan River and the surrounding canals, and laboratory tests were carried out. Investigations are being carried out on the commercial entities from which the above materials may be leaked.”

Arthur Beglaryan, who heads the Inspectorate’s Wildlife Management Division, told Hetq that they had taken numerous samples in the communities of Ararat Province where the storks are heavily contaminated. Samples were taken from the communities' waters - the Hrazdan River, the canals, and their swampy sections, where the storks were probably contaminated.

A laboratory study found that the birds had been contaminated with edible oil, but what the oil was and exactly from what commercial entity it had flowed from, Beglaryan could not say, noting that the studies were ongoing.

Institute of Zoology researcher Lyuba Balyan, in a conversation with Hetq, drew attention to the following.

A lab examination of the first sample found that only 20% of the pollution on the bird was oil. It could not specify what the remaining 80% was. Zoologists then transferred two stork feathers to the Inspectorate for study in another laboratory. Balyan said they expected to receive more detailed information from this examination

In a follow-up conversation with Hetq, Balyansaid they were still waiting for the results of the second laboratory analysis.

For his part, Arthur Beglaryan merely repeated his earlier statement.

"The Inspectorate’s laboratory has revealed that it is a nutritional oil. As to a detailed analysis of the oil, we have sent the case to the law enforcement agencies. Their lab should investigate and launch a criminal case if called for."

The Inspectorate has yet to announce any new developments after the second feather sampling. Beglaryan says he has sent all pertinent materials to law enforcement, including the feather samples.

When asked why the Inspectorate hasn’t been able to unearth specifics regarding the contamination, and whether its equipment was inadequate for the job, Beglaryan responded: “We cannot ascertain what the oil is specifically. Our equipment is lacking.”

Q - Why didn't you say as much at the time, that the Inspectorate’s lab doesn’t have the necessary capabilities?

Beglaryan – To begin with, our laboratory said that what was found in the stork’s feathers and what was found in the river was the same oil. As to what kind of oil, we couldn’t specify. Because there were indications of criminality, we sent allmaterials to the law enforcement.

Q – How old is your laboratory equipment?

Beglaryan - We have a specialized laboratory. We study wastewater that is discharged into the environment. But as to a detailed analysis of the oil, that may be a discharge, we don’t have the capability.

Beglaryan says that although investigations were underway (investigating the number of endangered storks, businesses operating in communities around the district), the collected materials were completely handed over to law enforcement, and they could not publish anything "due to the confidentiality of the investigative materials."

As a matter of fact, as Hetq mentioned at the beginning, only case materials are being prepared. No criminal case has been launched and no preliminary investigation is underway.

This means that the Inspectorate sees its role in the matter as finished. The Inspectorate confesses that it has only been able to determine that some of the material contaminating the storks is edible oil.

A chain of contradictions: words versus reality

Beglaryan didn’t wish to comment on our observation that some environmentalists consider the situation an environmental catastrophe, noting that such an evaluation must have a scientific justification.

Strangely, just three days ago Beglaryan told news.am that the decline in stork numbers was inevitable, and they had predicted it.

"We labelled it an ecological disaster. We knew they were going to decline. Some storks can't fly. They can’t get food and inevitably die.”

In late July, Karen Aghababyan, a legal adviser to the Minister of the Environment, posted on Facebook that cleaning the storks with new reagents was more effective than the previous method (soap solution).

"Thus, next Sunday (August 4) we will have to organize a big clean-up for the storks,” his post read.

Recently, however, Beglaryan told news.am that it is not possible to wash the storks’ feathers. "The feathers are damaged when washed and the result is the same,” he said.

In response to a Hetq inquiry, the Ministry of Environment said that oil-soaked storks were found in eleven villages in Ararat Province - Hovtashen, Hovtashat, Hayanist, Zorak, Dashtavan, Sipanik, Sayat-Nova, Darakert, Darbnik, Noramarg, Nizami.

A troubling situation has also been recorded in waters adjacent to the villages, according to the following environmental statement sent to Hetq.

"The Ministry's Environmental Monitoring and Information Center SNCO conducts water quality monitoring every month near the Darbnik and Geghanist villages of the Hrazdan River, as well as near the riverbank, as a result of which we often find poor water classified as 5th grade. On July 23, 2019, ministry specialists sampled water from the Hrazdan River in the Khachpar village of Ararat Province. Laboratory research has shown that the water is contaminated with large amounts of organic matter, phosphate and ammonium ions.”

Despite the government’s failure to pinpoint the sources of the pollutants contaminating the storks, officials declared that they had indeed done just that.

In late July, Karen Aghababyan wrote the following:

"The source of the pollution is probably the sturgeon fisheries, which dump the internal organs, containing large amounts of oil into the rivers. These dischargesaggregate in the canals and the storks in these spots, looking for food, are contaminated. This theory requires confirmation, after which the fish farms should be forced to clean the canals and find other means of managing their waste.”

Earlier this month, Aghababyan noted that: "During our last hike we found a real source that pollutes the aquatic ecosystem and white storks. The process of cleaning up the canal started today. I congratulate us all.”

At the same time, the Ministry of Territorial Administration and Infrastructures’ Water Resources and Infrastructure Committee announced that Melioration CJSC was cleaning up the second site of the Hrazdan River riverbank collector.

“The whole network is 6800m long, but the most polluted is the open drainage network coming from the Sis community at the intersection of the Sis-Noramarg-Ranchpar communities, where a real garbage sump has been built under the bridge. The large diameter pipe coming from the Nairit Plant and the non-functioning drainage pipe also contribute to the waste back-up. The accumulated garbage is the fat from the fish farms, which, by the way, has become a nuisance for storks in recent days."

The Committee noted that 30 tons of rubbish had been cleaned in one day, but there was a need to clean the three times that amount.

But the real issue is not one village, one collector and one pipe, as various government agencies seem intent on focusing on.

Some of the eleven villages mentioned by the same ministry are 11-13 km (north) above the crossroads of Sis-Noramarg-Ranchpar communities, signifying that even tons of garbage in a single collector cannot be the sole cause of stork contamination in all villages. This is simple logic.

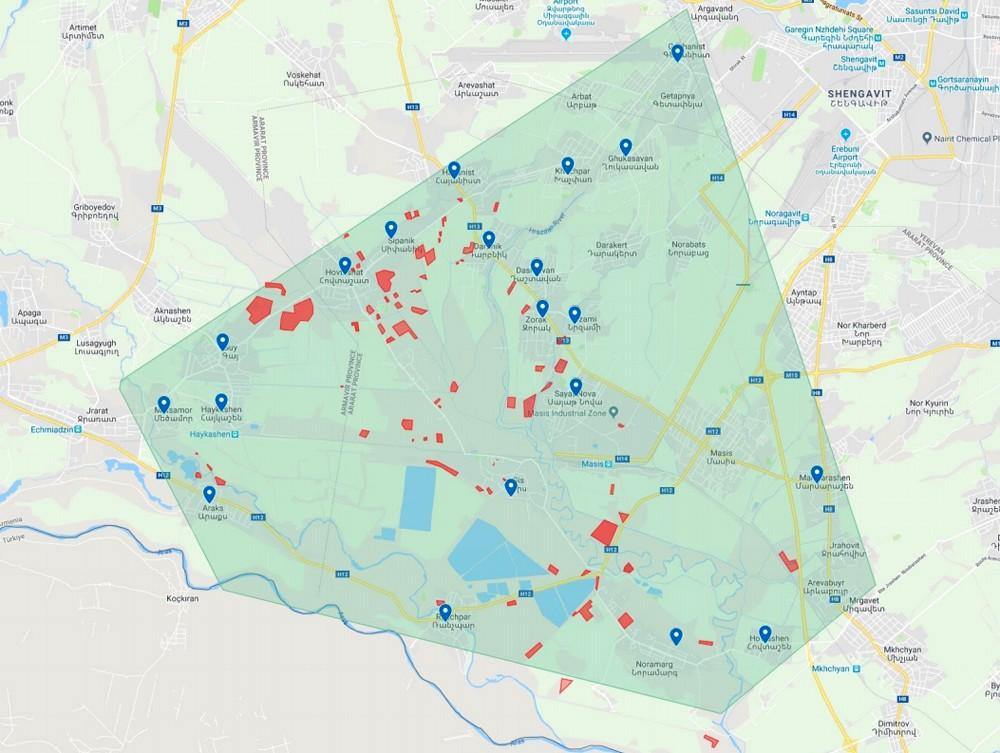

What's more, researcher Lyuba Balyan provided Hetq with a map of the Institute of Zoology listing all the places where blackened oil-coated storks were found. On the map, they tried to show the scale of the environmental disaster. The twenty villages of Masis, Artashat and Etchmiadzin with contaminated storks are marked in blue, while the red marks indicate fish farms.

Balyan says they cannot say who these fish farms belong to, noting that such work must be carried out by relevant government authorities.

Lack of government attention and targeted actions

The zoologist notes that while the communities in Ararat Province were in the public spotlight after the first alert, specifically Hovtashen, where many contaminated storks were found, many storks were left out of the spotlight.

The fact is that many birds nest on electricitypylonson the edges of roads outside residential areas. To date, according to Balyan, no monitoring has been conducted by any state agency in this direction.

“We were walking around these communities five days ago to find out what condition the storks are in. There’s been a decrease in the number of contaminated storks. This is a bad sign. Most have probably died,” says Balyan.

Balyan noted that two storks fell into the canal and died in Hovtashen. She says that when a bird dies of starvation it can become another animal’s prey. In this case it is not possible to record the stork deaths, as any traces will not be found.

The researcher says that this whole topic has not received enough government attention and clear action.

Balyan says the only positive outcome was the response of volunteers who formed teams to clean the storks.

"But even this is shameful because such a question should not be solved solely by volunteer forces. The work should have been a bit more operative; a more serious solution was required. In addition, they did not consider that cleaning the animals is a zoologist's job. There are safety factors involved. They allowed people to approach the animals without knowing in advance whether the animal was diseased. The whole thing as a bit unregulated."

Balyan argues that the cleaning of the birds was lacking,only organized on the weekends. The researcher points out that if an on-site team or commission had been operating every day for two months, it would have been possible to increase the number of storks saved by 50%-60%.

“There will be some decline in the new stork numbers this year. If the monitoring is carried out at such a rate and potential as it is today, I think that more than 100 storks will not be able to survive,” says Balyan, adding that 1,000-1,200 storks winter in Armenia each year.

Given this summer's developments, it will be important to keep track of the number of storks wintering in Armenia.

Only then will the true magnitude of the problem be revealed.

Videos

Videos Photos

Photos

Write a comment